Chord progressions are fundamental to the understanding and appreciation of jazz music. Jazz standards are constructed using these chord progressions, many of which are common thematic patterns throughout the genre. For that reason, learning to identify and play over these progressions is foundational to your study as a jazz musician.

So, what is a chord progression? A chord progression is a series of chords played in sequence. These progressions set a songs harmonic structure, and when combined with a melody, they create lead sheets for jazz standards.

Jazz theory gives us some common functional chord progressions that are used across many songs. By practicing these common progressions in different keys and styles, you will automatically improve your ability to play standards as well.

The 7 most important chord progressions in jazz #

You may have heard of the “four chord song” by comedy musical group Axis of Awesome. In this act they demonstrate how the same 4 chords are used over and over in hit popular songs.

In the same way, jazz has 7 foundational chord progressions that make up virtually every jazz standard you’ve ever heard. In my experience, these building blocks are 90% of the material you will encounter in your playing.

The most foundational chord progressions in jazz are:

| Chord Progression | Common Name | Example |

|---|---|---|

| V-I (or V-i) | "Five-One" | G7 - C |

| ii-V | "Two-Five" | Dm - G7 |

| ii-V-I | "Two-Five-One" | Dm - G7 - C |

| Secondary Dominant | "Five of Five" | D7 - G7 - C |

| Tritone Substitution | "Tritone Sub" | Db7 - C |

| I-IV | "One-Four" | C - F |

| IV-iv | "Nostalgia Chord" | F - Fm |

Step-by-Step Video Training

As a premium member of Jazz-Library you will have access to our Jazz Fundamentals video course which has 70+ video lessons teaching you these micro-progressions, song forms, chord voicings, comping rhythms and more.

You’ll find these short chord progressions literally everywhere in jazz. In fact, many jazz standards are constructed completely from those progressions.

It’s essential to practice these progressions regularly, in every key. Use them as exercises to learn new techniques, and practice finding them in your favorite standards.

As with everything in jazz, I find it helpful to think in small chunks. By taking the time to master each of these small movements and forms in each key, you’ll be able to pick up almost any tune you can think of.

Let’s break each of them down individually. The following examples are each in the key of C, to make it easy to follow. Be sure to practice these in each key to build fluency.

The V-I “five-one” chord progression #

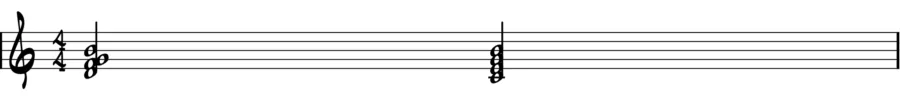

The most important chord movement is from the V to the I — the dominant to the tonic. Music is a journey of leaving home (the tonic), going on a journey and returning back home. The dominant paves the way home. It creates tension with voice leading that resolves perfectly back to the tonic.

In the key of C major, the V chord is a G7 which leads to the Iof C. Listen to the tension within the V chord and how that tension is resolved by moving to the I. It’s like you take a deep breath in, hold it, and then release that tension back into the world.

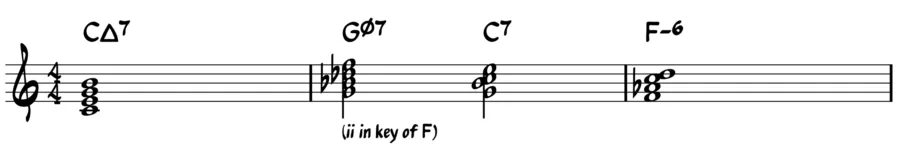

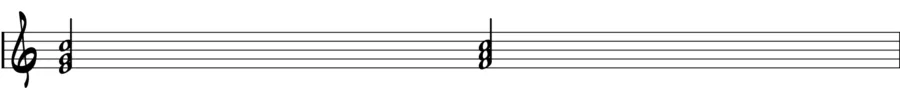

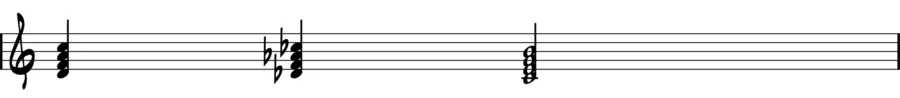

Major V-I: #

The same chord movement applies when you are in a minor key. In that case, the V stays dominant, but the i is minor.

Minor V-i: #

Note that in the minor keys, the i chord is traditionally a 6th chord, not a minor-7th.

The ii-V “two-five” chord progression #

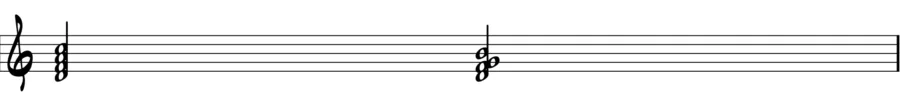

Like the previous V-I progression, the ii-V also resolves by going down a fifth interval. For example, in the key of C the ii chord is D and the V chord is G. This movement by a fifth is very natural.

The ii-V chord progression does not resolve on its own. The V7chord creates dissonance that needs resolution. For that reason, the ii-V is often a movement that sets up some kind of resolution.

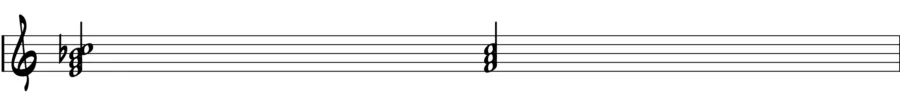

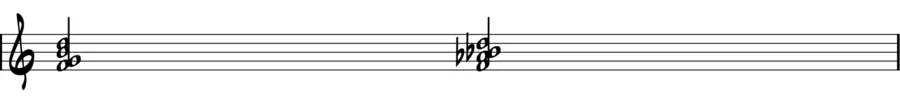

Major ii-V: #

Quite often, the ii-V just sets up a V-I. This creates the most common chord progression in all of music, the ii-V-I, which we’ll talk about on its own down below.

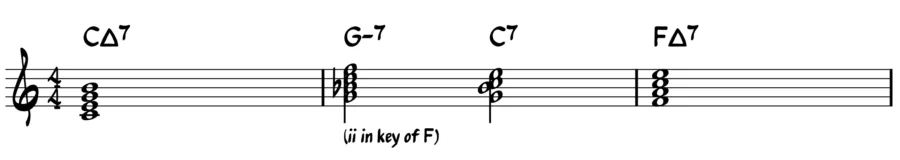

But, a ii-V chord movement is also a great way to move briefly into a different key. For example, lets say we are in the key of Cbut we want to shift temporarily into the key of F for a few bars. We can do this naturally by playing a ii-V in the key of F:

The Gmin and C7 chords don’t belong to the key of C, but rather to F, and so this ii-V is a simple path to the new key.

Minor iib5-V: #

The ii-V in a minor key works the same as major, except that the ii chord is half-diminished instead of minor. (See Modes of the Major Scale to understand why.)

Like we did above, we can use the minor ii-V to temporarily shift into a minor key. Let’s use the same example from above, where we start in C major but shift to F. But this time, let's move to Fminor.

This movement is really similar to the major ii-V. In fact, only note has changed.

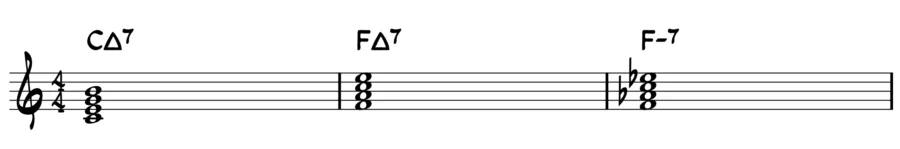

The 2-5-1 “two-five-one” progression. The most important progression in all of music.

| Chord | Example (major) | Example (minor) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | minor-7 | minor-7-b5 (half-dim) |

| 5 | dominant-7 | dominant-7 (with b9) |

| 1 | major-7 | minor-6 |

The quintessential jazz chord progression, the ii-V-I, is just the two previous progressions squeezed together, the V-I, and the ii-V. Functionally, the progression can bring you home to the tonic, establish a new tonal center, or provide ways to dress up existing harmonies.

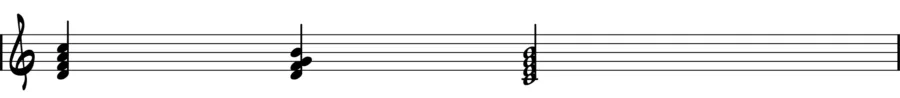

Major ii-V-I: #

Minor iib5-V-i: #

I find it helpful to learn your ii-V-I with both your hands, and with your eyes. By that I mean you should build the muscle memory in your hands to play these progressions on auto-pilot, but also to train your eyes to identify them in lead sheets.

The benefit of this is that when your eyes see the progression, your hands already know what to do. Over time you begin to understand this progression as a single concept — a “251” — instead of 3 separate chords.

Secondary Dominant #

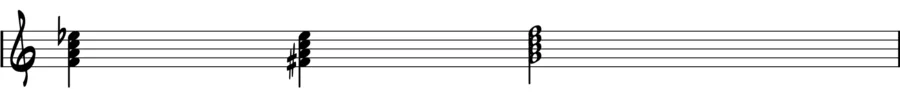

There’s a common variation of the ii-V called a secondary dominant. In that case you exchange the minor ii chord for a dominant II. The II-V is actually a V-I resolving to the dominant key instead of the tonic. For that reason, this is also called a “5 of 5.”

This gives your playing a bit of a “lift” as this dominant II chord isn’t in the current key. Even so, because it’s a dominant chord a resolution down a fifth is expected.

These often chain even further, such as in the B Section of the Rhythm Changes (see below). Experiment with a adding more dominant chords in front, creating a “5 of 5 of 5” or even “5 of 5 of 5 of 5”. (Saying this is quite a mouthful! That’s why we simply call this a “turnaround”).

The 1-4 “One-Four” chord progression. #

The movement from the I to the IV chord is also very common. We’ve talked a lot about how V-I and ii-V progressions work so well because they move by a fifth interval. Well, the same is true for I to IV as well since the IV chord is a fifth below the I.

Often times you’ll see the I chord changed to be a dominant chord instead of major. By doing that you make this into a V-I progression. (C7 is the V chord in the key of F).

The 4-5-1 “Rock and Roll” chord progression #

In a major key, the IV, V and I chords are all based on major triads. Both the IV and the V are a fifth away from the I and so these chords all feel at home together.

The 4-5-1 is the basis of the blues, and as the blues turned into rock, it's become the foundation of our rock and roll music.

Breaking from diatonic harmony, blues players usually make all 3 chords dominant chords. This makes each of them feel unresolved, anticipating the next chord. This creates a perpetual cycle of unresolved chords, which is the essence of the blues.

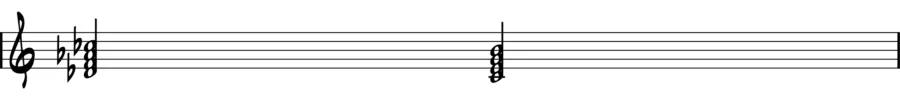

Moving from 4 to 4 minor (IV-iv) #

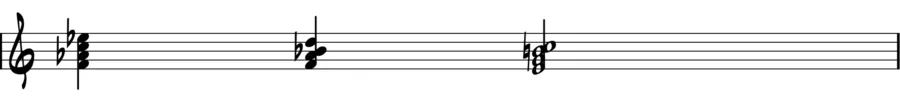

In a major key, its quite common to change a IV chord (major) into iv (minor). This 4-minor chord is a "borrowed chord" since it's outside of the current key, but shares the same root note.

The 3rd of the iv chord is the flat-6th of the key. Adam Neely calls this b6 the "nostalgia" note since it was so commonly used for this reason in musical theater.

Tritone Substitutions #

We can alter these V-I and ii-V-I progressions by substituting the V for the note a tritone away, the flattened ii. Both the 5 and the bii have the same notes for the 3rd and 7th, which makes the root note the primary difference between them. The voice leading from the b2 to the I is a very strong semi-tone movement, known as a leading-tone.

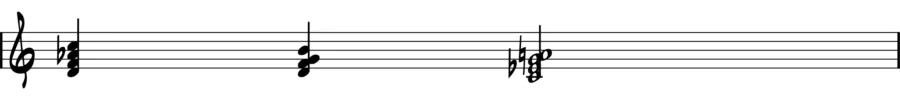

Major V-Iwith Tritone Substitution:

Tritone sub for ii-V-I:

These tritone substitutions can be a bit tricky to spot at first, but there's an easy trick to identify them. Look for a dominant chord which resolves down a half-step. That dominant chord will be the tritone! For example, if you see an F#7 resolving to F, then you can be sure the F#7 is a tritone substitution (for C7).

Backdoor Progression #

There is another variation of the ii-V-I called the "backdoor." This progression is also quite common, but requires a bit more exploration to understand.

The backdoor is built on the premise of substituting the V chord for another chord, a dominant 7th chord built on the b7 of the key. In the key of C, that would substitute a G7 chord for a Bb7.

If you take a look at the two chords side-by-side you'll notice there are common tones between them, the D and the F. The other two notes in the G7 chord, G and B, only move slightly by a semitone each to Ab and and Bb.

Basing the progression around the Bb7 as the V, we can reverse engineer that the ii chord needs to be Fmin. The resulting progression, Fmin-Bb7-Cmaj, is a resolution from the plagal side of the Circle of Fifths (the opposite direction of the ii-V-I) and thus is called the "backdoor."

To simplify this for practical playing, most jazz players I know think of this as a ii-V in the key a minor 3rd above the root (Eb in the key of C).

The backdoor progression certainly sounds different than its cousin the ii-V-I, but yet because of the strong voice leading, it resolves confidently.

Diminished Passing Chords #

If you ever want to move from one chord to another chord a whole step away, you can stick a diminished chord in between them. This is a technique used by lots of standards, but it always reminds me of the opening sequence of Ain't Misbehavin'.

Diminished chords are inherently unstable and like to resolve by half-steps. For the reason, this works almost universally with any quality of chord.

The example below is a classic bluesy maneuver, moving from IV to #4dim to V7.

Chord Progressions Are Relative To Their Key #

When we look at lead sheets and real books, chords are notated with their letter names. But, when we study the progressions we should number them using Roman Numerals based on their position in the key. This is because chord progressions are relative to the root of the key, and apply equally across all 12 keys.

For consistency in this article I’ve written each progression in both its Roman Numeral form, as well as its application in the key of C.

Connecting 2-5-1's by Whole Steps #

Lots of jazz standards temporarily modulate to the key a whole step below their current root. Using ii-V-I's, this is a quite natural movement. After landing on the I, you can keep the same root note but make the chord minor, which becomes the ii in the ii-V-I for the key a step down.

For example, we can start with a ii-V-I in C: Dm-G7-C and then turn the C into Cm, making a ii-V-I in the key of Bb: Cm-F7-Bb.

You can find this pattern used in tunes like How High the Moon, Solar and Cherokee.

A popular way to use this technique is to move from a major I to the major II. This II chord is non-diatonic -- not belonging to the original key -- but you can bring it back home to I following this same technique. This technique was popularized by The Girl from Ipanema and Take the A Train.

Take the A Train:

Turnaround Progressions #

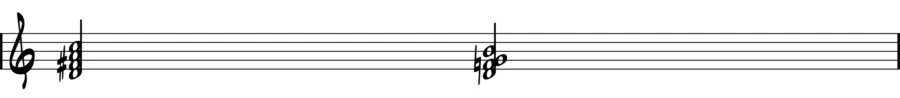

A turnaround is a way to bring your song back home to the tonic by walking back through the circle of fifths.

As we've learned, a ii-V-I is just progression through resolving chords by fifths. The ii down a fifth to the V, down a fifth to the I. The turnaround just extends this by adding more chords to the front of the cycle. For example, the vi-ii-V-I introduces a vimoving down a fifth to the ii, and then continuing through the ii-V-I cycle. It can be extended further into a iii-vi-ii-V-I as well.

It's is most true form, these turnarounds are built diatonically from the key, with the ii & vi chords as minor, the V chord as dominant and the I chord as major.

The basic turnaround progression: 6-2-5-1 #

An extended turnaround progressions: 3-6-2-5-1 #

Like we did with secondary dominants back in the section on ii-V-I's, any of the chords in the sequence can be changed into dominant chords to create more "pull" towards the following chord.

Altering the turnaround with secondary dominants #

We can take any of the minor chords in the turnaround and change them into secondary dominants, as illustrated below with the basic and extended turnarounds:

Introducing tritone substitutions into the turnaround: #

Like the Tritone Substitution we explored earlier, any of these dominants can be substituted for the tritone as well. Here's a common version that uses secondary dominants and tritone substitutions to create a chromatic bass line:

Chord Progressions for Standard Jazz Forms #

So far we've talked about chord progressions which are used as building blocks for standards. But, the opposite is also true. Sometimes we take a popular tune, extract the chords from that tune as its own progression, and build more tunes on top of it.

The most common reusable song forms in jazz are the blues, and Rhythm Changes.

The 12-Bar Blues Form #

Here's the form for a standard 12-bar blues:

| Measures | Chord |

|---|---|

| 1 - 4 | "I" chord. |

| 5 - 6 | "IV" chord |

| 7 - 8 | "I" chord |

| 9 | "V" chord |

| 10 | "IV" chord |

| 11 - 12 | "I" chord |

We can't have a discussion about jazz chord progressions without talking about the blues. The 12 bar blues form is a conventional set of 12 measures built using I, IV and V chords. The standard form has been used countless times through the blues genre, but also in all forms of music that have built from those roots.

Classic rock and roll tunes, such as Johnny B. Goode (Chuck Berry), Hound Dog (Elvis), Rock and Roll (Led Zepplin), Tutti Frutti (Little Richard) and I Got You - I Feel Good (James Brown) are written on top of the following classic 12 bar blues form:

As musicians have brought their own ideas and influences to the blues, they've extended and modified it to fit their desires. Each of the ones that follow are still rooted firmly in the original form, but have been extended with turnarounds, intermediate chords, extended voicings and more. But, in each case, it's still very much "the blues."

Here are a few of the most common variations of the blues. The first is a slight variation with a I-IV quick changes, and a secondary dominant added to create a turnaround:

Count Basie took this a step further introducing a #4dim passing chord:

Bebop players explore "outside" the changes by introducing ii-V's in front of the IV and ii chords.

Tritone substitutions are added on some V chords to give chromatic base movement:

Charlie Parker shows his brilliance by introducing more ii-V's, minor ii-V's, and chromatic dominant chords. This has become known as "Bird's Blues."

"Rhythm Changes" #

In 1930, George and Ira Gershwin published I Got Rhythm as part of the musical Girl Crazy, It was a huge sensation, but it wasn't until 1945 when Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie first recorded Anthropologie, based on the same chord structure, that the tune was immortalized as a jazz standard.

These changes are the foundation for dozens, if not hundreds, of other jazz standards including Anthropology, Oleo, Cheek to Cheekand even the theme song for The Flintstones.

The Rhythm Changes are actually 2 chord progressions, an A and B section, put together in an AABA form.

A Section:

The first section of Rhythm Changes is the turnaround we learned earlier (with a secondary dominant).

B Section:

The second section of Rhythm Changes is the extended 3-6-2-5-1 progression (using secondary dominants.

How to practice chord progressions #

Take a look through both the 12 Bar Blues and the Rhythm Changes and you'll notice the chord progressions we focused on so intently.

- The 12 bar blues is full of

I-IV, andV-Iprogressions. - The A section of the Rhythm Changes is just a

vi-ii-V-Iturnaround - The B section of the Rhythm Changes is also a turnaround using secondary dominant:

III-VI-ii-V-I

Building your practice routine around these progressions will tactically install them into your muscle memory. Your ability to intellectually recognize them in other contexts will allow that muscle memory to apply to those tunes almost automatically.

Take the time to internalize these core progressions and build them into your practice routine. Happy practicing!