The tritone substitution is a fundamental concept in jazz harmony. We hear these substitutions throughout the catalog of great recordings, and find them in songs in our Real Books and The Great American Songbook.

So, what is a tritone substitution?

A tritone substitution is when we substitute one dominant seventh chord with another which is a tritone away. This substitution introduces a chord from outside the key, which enriches the harmonic texture of the song.

In this article, we’ll break down the tritone substitution, step by step. We’ll delve into the mechanics of how it works, its history, and, most importantly, its application in jazz harmony. By the end, you will understand what a tritone substitution is and have practical exercises to master this technique in your own playing.

My discovery of the tritone substitution #

When I listened to my favorite jazz albums, I was intrigued by a dominant sound. It had a unique, “outside” sound that brings us back to the tonic using notes from a different key. I would listen to the classics, like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and transcribe their solos to understand the secret behind this sound that I loved so much. And, for the longest time, this sound eluded me.

Then, I learned about tritone substitutions. It was a revelation, like finding the missing piece of a puzzle. This simple chord substitution trick was the key to that dominant sound that had long intrigued me. It turned out the concept was pretty simple to understand and even easier to put into practice. Very quickly, my own playing started to sound more and more like those recordings I cherished.

As we delve deeper into the mechanics of tritone substitution in the following sections, we'll uncover how this simple concept can significantly enhance your playing.

History of tritone substitution #

The tritone substitution has deep roots in the classical tradition, long before Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie started incorporating them into Bebop.

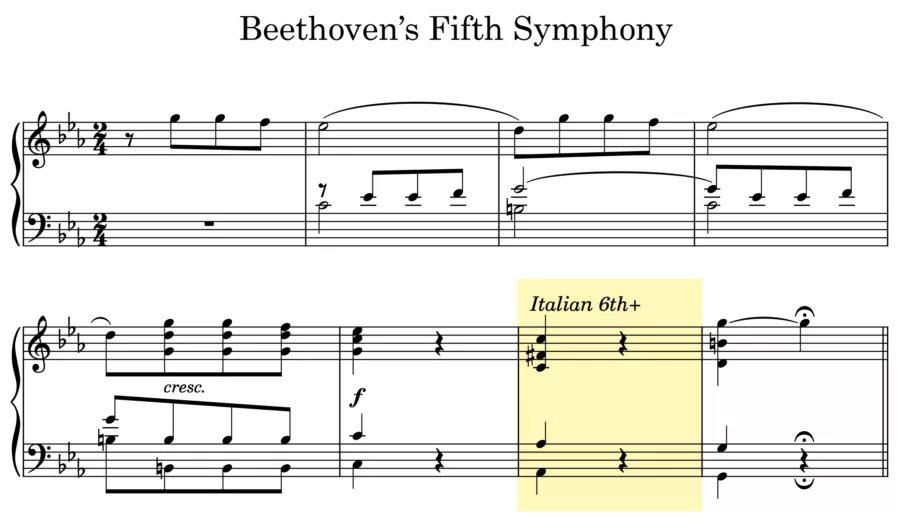

If you’ve studied classical harmony, you may know about augmented sixth chords -- the French sixth, the Italian sixth, or the German sixth. While different from the modern tritone substitution, the fundamental harmonic principles that made these augmented sixth chords function are the same.

See this famous example of a Italian sixth from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony:

For more about the augmented sixth, check out this great resource by Robert Hutchinson.

The impact of tritone substitutions on modern jazz cannot be overstated. They have become a staple in jazz improvisation and composition, offering a distinct sound that resonates with the spirit of jazz. From the hard bop of Horace Silver to the modal explorations of Miles Davis, to neo-soul players like Robert Glasper, tritone substitutions have continued to shape the harmonic landscape of jazz.

The tritone interval #

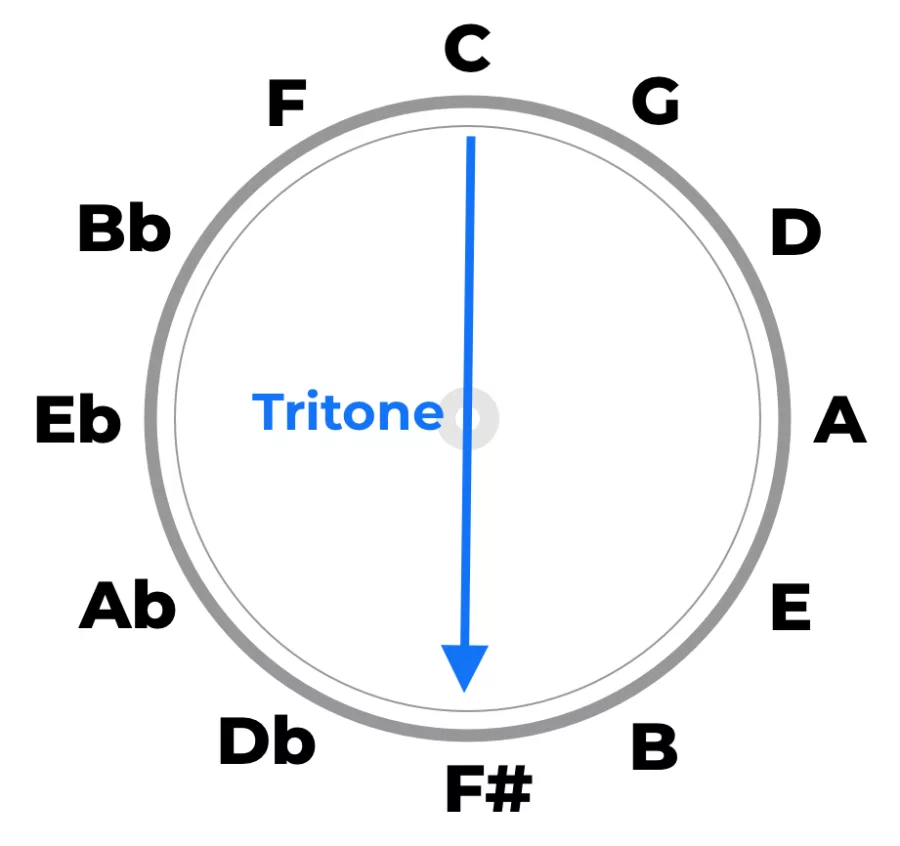

This tritone interval is the key to understanding tritone substitution.

The tritone interval spans three whole steps, or six half steps. I suggest thinking of this as an augmented fourth (#4) to make it faster to find.

Notice how the tritone interval perfectly splits the octave in half. There are 12 notes in our chromatic scale, and the tritone occurs halfway, at the 6th note. Because of this, the same tritone exists from two perspectives:

- From F to F, the tritone B splits the octave

- Similarly, from B to B, the octave is split by its tritone F.

It is critical that you see this tritone from both perspectives, because it’s the key that unlocks how the substitution works.

What is a tritone substitution? #

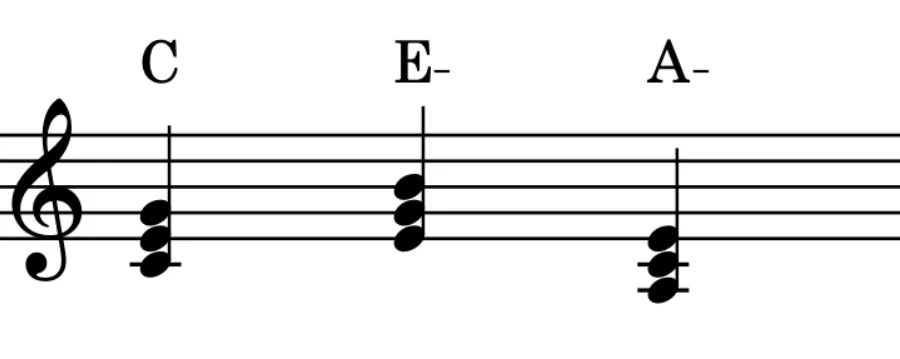

One of the most common ways to substitute one chord for another is by finding a chord that shares common tones with the original.

For example, we might substitute C major for E minor, because the two chords share 2 of the same notes. Similarly, we could substitute C major for A minor.

The tritone substitution is another way to do this. We’re going to take a 4-note 7th chord and substitute that chord for another which has 2 notes in common. Those two shared notes will make the chord “fit” the sound of the chord it's substituting. But the two other notes will change to notes from a different key, which gives the chord its “outside” sound.

Tritone substitutions are almost exclusively applied to dominant chords, because dominant chords contain the tritone interval within them:

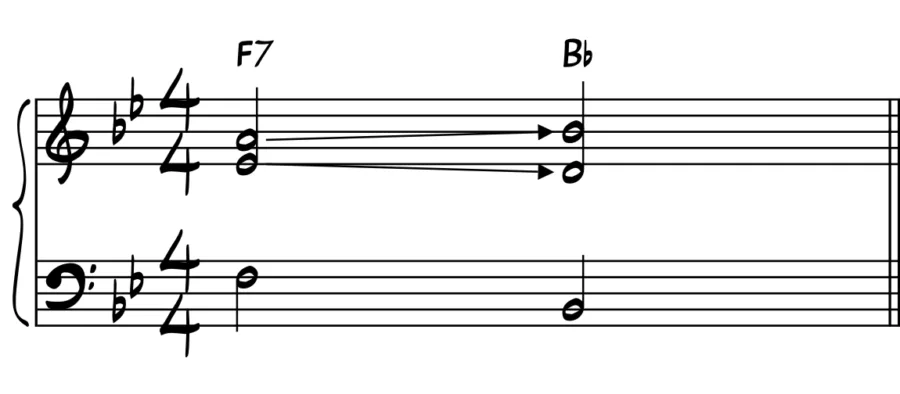

The F7 chord (F, A, C, Eb) includes the tritone of A-Eb.

As we learned, the tritone exists from two perspectives, and so we can see that another chord has the same tritone within it.

The B7 chord (B, D#, F#, A) includes the tritone of D#-A (Eb-A, enharmonically), which is the same as in F7.

As you can see, the F7 and B7 chords have 2 notes in common, A and Eb, but the other two notes in each chord are from completely different keys. F7 belongs to the key of Bb, and B7 belongs to the key of E.

Note: Interestingly, the keys of Bb and E are also a tritone apart – isn't math fun?

Let’s break it down step by step:

Step-by-Step Video Training

As a premium member of Jazz-Library you will have access to our Jazz Fundamentals video course which has 70+ video lessons teaching you comping rhythms, chord voicings, soloing strategies and more.

Finding the tritone substitution #

To gain a deeper understanding of the substitution, let’s proceed slowly and dissect the example of substituting F7 with B7 in a step-by-step analysis:

- Identify the original chord and its function: The original chord in our example is F7. In the context of the tonic key of Bb major, F7 functions as the dominant (V7) chord, creating tension that naturally resolves to the tonic, Bb major.

- Examine the tritone interval in the original chord: In F7, the tritone interval is between A (the major third) and Eb (the minor seventh). This interval is critical as it creates the chord's dominant character and tension.

- Locate the substitute dominant chord: This substitution is found a tritone away from F7. In this case, the interval between F and B is the tritone, so B7 is our tritone substitution.

- Analyze the tritone interval in the substitute chord: In B7, the tritone is between D# (the major third) and A (the flat seventh). Notice the reversal of roles: the A and Eb are the same notes that formed the tritone in F7, but their roles as the third and seventh are swapped. (D# and Eb are enharmonically the same note.)

- Understand the resolution mechanics: Despite the chord change, the tritone interval (Eb and A) in B7 resolves in the same way as it does in F7. Eb resolves down to D (the third of Bb major), and A resolves up to Bb (the root of Bb major). This maintains the same voice- leading resolution as the original F7 to Bb major progression, despite the harmonic color being different due to the change in the bass note (from F to B).

- Apply and listen: Finally, apply this substitution in a musical context, such as a ii-V-I progression, and observe how the bass note B introduces a chromatically rich twist before resolving smoothly into the tonic chord. (More on the ii-V-I below)

Example on Autumn Leaves #

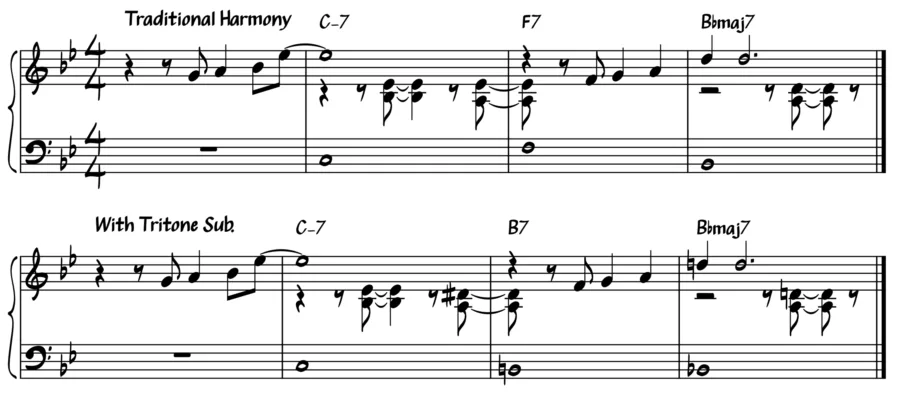

Let’s apply this concept to a real-world example:

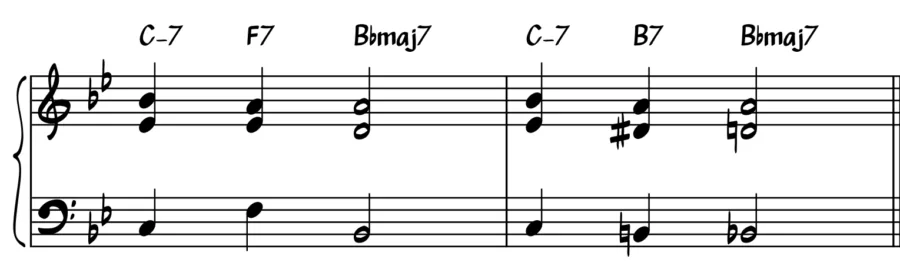

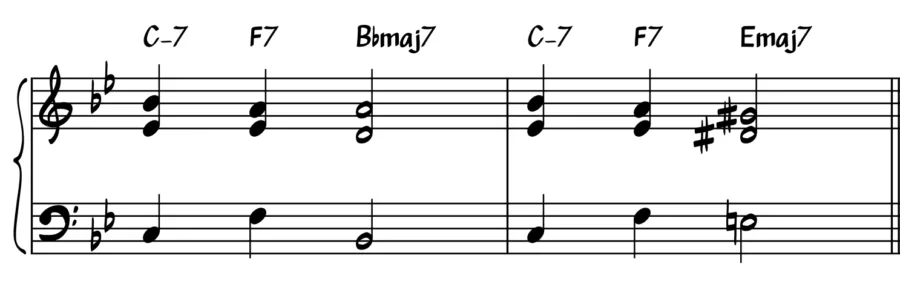

In the standard “Autumn Leaves,” the A section starts with a ii-V-I in Bb major (Cm7 - F7 - Bbmaj7). Applying our tritone substitution to the F7, we end up with a ii-bII7-I progression (Cm7 - B7 - Bbmaj7).

Take special note of the chromatic bass line resulting from this substitution. The chromatic movement is what makes the tritone substitution so compelling.

The function of dominant chords #

Dominant chords play a distinctive musical role due to the inherent tension created by their leading tones. In the context of our F7 chord, the important chord tones are A and Eb. The A, being the third of the F7 chord, naturally resolves up by a half step to Bb, the root of the tonic chord. Simultaneously, the Eb (the flat seventh of the F7) resolves down by a half step to D, the third of the tonic chord. The voice leading created from F7 to Bb major creates compelling “gravity” that virtually begs for resolution.

When we apply a tritone substitution, such as replacing F7 with B7, this voice leading acts the same way. Both chords contain the same tritone (A and Eb/D#, enharmonically), and they resolve using the same half- step voice leading. As a result, the two chords serve essentially the same musical function.

Indeed, the root movement is the biggest difference between the chords. That opens us up to the two fundamental resolutions for dominant chords:

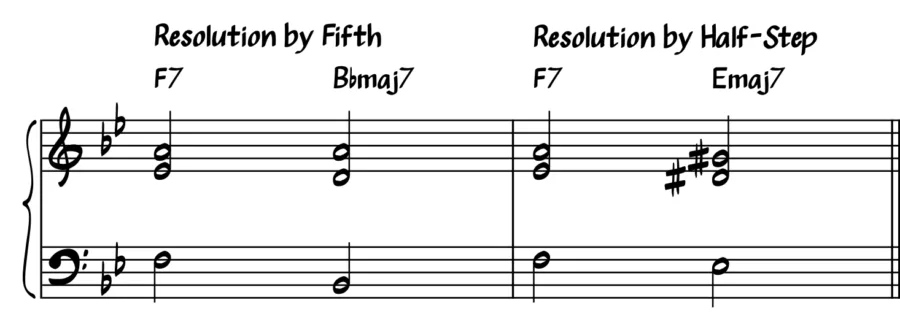

Resolution by Fifth #

In the most traditional use, a dominant chord resolves down by a fifth. After all, the V chord is built using the notes from the 5th mode of the major scale, making it logical for it to resolve down by a fifth.

This resolution could be a V-I, diatonic to the current key, or function effectively as a secondary dominant.

Resolution by Half-Step #

Thanks to tritone substitution, dominant chords can resolve down by a half-step just as effectively. In this scenario, the dominant chord is non-diatonic, offering an opportunity to incorporate outside harmony.

Using the tritone substitution to modulate #

With these two resolution options for chords—by fifth or by half-step— we can simply modulate to another key by using the opposite resolution from what is expected.

For example, as we've seen, we can substitute the V chord in a ii-V-I progression with its tritone counterpart. In the key of Bb, we can substitute the F7 for B7:

However, instead of changing the V chord, we could keep the chord the same and substitute its function. In this example, we could retain our F7 as is, but choose to swap its function with that of its tritone—resolving down by a half-step rather than by a fifth. As a result, we end up with Cm7-F7-E major!

We’ve modulated away from the key of Bb and into the key of E—the key a tritone away.

The bass is the only difference #

In a jazz ensemble context, where piano or guitar players often use rootless voicings, the bass player actually has significant control. They can decide to change a V chord to its tritone substitute simply by changing the bass note. The piano or guitar players don’t even have to change the chords they are playing, so the bass player can do this spontaneously in the moment.

(Though a good pianist would recognize the change and perhaps alter their harmony too, that's something that comes with experience.)

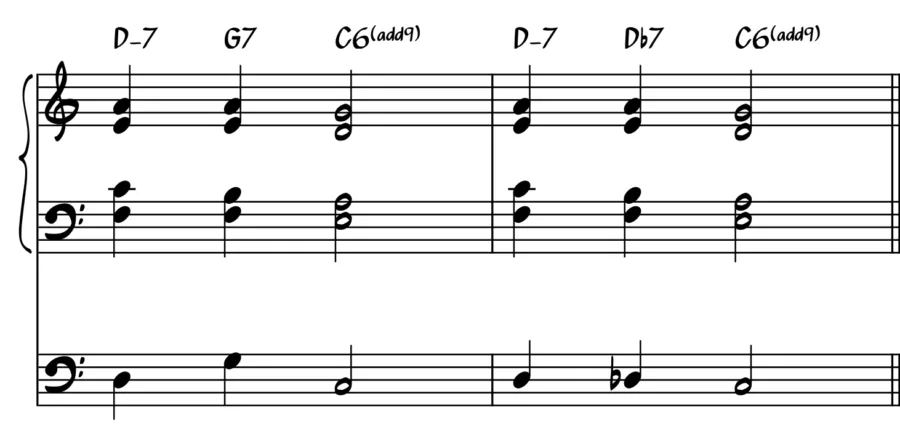

Bass player example:

Consider a piano trio playing a ii-V-I progression, where the piano player might use rootless voicings that focus on the chord’s upper extensions and omit the root note.

Typically, the bass player outlines the root notes of the chords, playing D (for Dm7), G (for G7), and C (for Cmaj7) in our example.

During the G7 chord, the bass player can opt to play Db instead of G. This single note change effectively turns the G7 into a Db7 from an auditory perspective, without the need to alter the piano's voicing.

This subtle yet impactful choice by the bass player seamlessly introduces a tritone substitution. While the rest of the band continues as planned, the overall sound changes significantly, showcasing the power and flexibility of tritone substitutions in a group setting.

Tritone substitution table #

Below is a table displaying all possible tritone substitutions. This serves as a quick reference chart to assist you in learning:

| Original Dominant Chord | Tritone Substitute |

|---|---|

| C7 | Gb7 |

| C#7/ Db7 | G7 |

| D7 | Ab7 |

| D#7/ Eb7 | A7 |

| E7 | Bb7 |

| F7 | B7 |

| F#7/ Gb7 | C7 |

| G7 | Db7 |

| G#7/ Ab7 | D7 |

| A7 | Eb7 |

| A#7/ Bb7 | E7 |

| B7 | F7 |

Tritones and the circle of fifths #

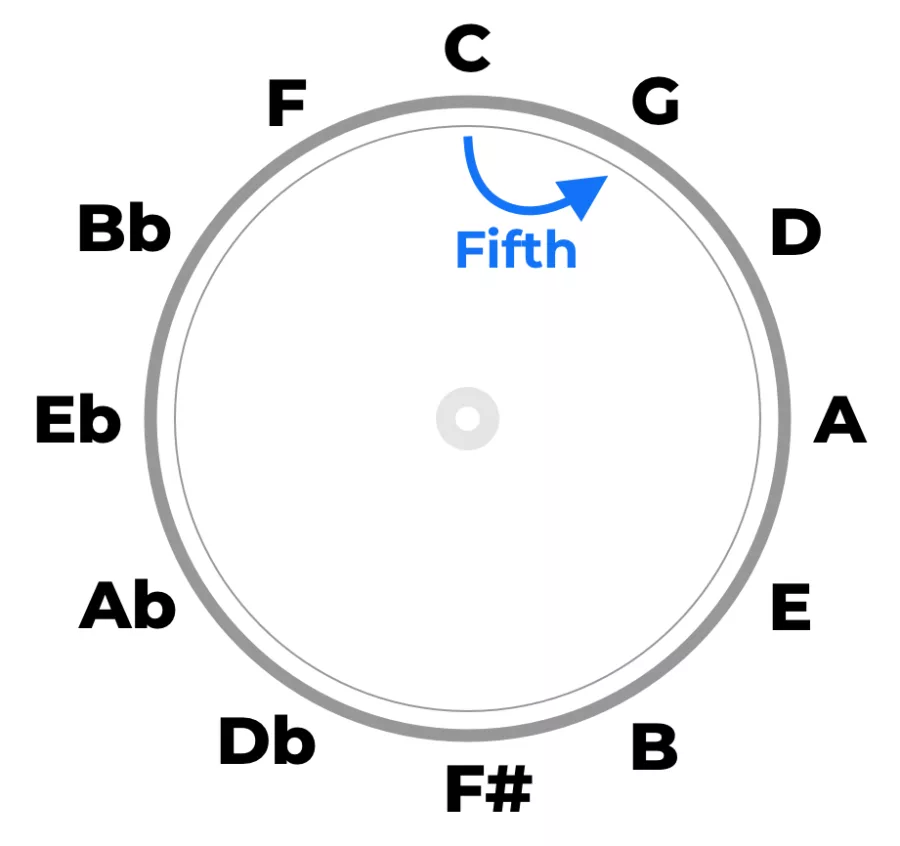

The circle of fifths is a fundamental concept in music theory, illustrating the cyclical relationship between keys. As we learned above, chords like to resolve down a fifth, and by chaining those together, we create a circle that connects all keys.

The circle of fifths can also be used to visualize tritone substitutions:

I find it helpful to understand the relationship between various keys through the harmonic connections created by these substitutions.

Scale choices for tritone substitutions #

The use of these non-diatonic notes, or notes from 'outside' the key, is particularly exciting for improvisation. It allows musicians to create momentary tension by using notes that don’t 'belong' to the current key, before resolving back to familiar territory. This technique opens up a world of improvisational possibilities, enabling soloists to weave in and out of the conventional scale creatively.

Have you ever heard a solo over a familiar tune, but then the musician injects a line of unexpected notes that knock you off balance, before resolving back to the familiar harmony? (This kind of move usually induces wails and stank face from the audience.)

That's the power of tritone substitution: it not only changes the harmonic landscape but also expands what is possible melodically. The tritone, being outside of our current key, opens up more notes that ramp up the tension.

In the bebop era, this technique became a cornerstone for jazz musicians, pushing the boundaries of harmony and improvisation. Tritone substitutions provided a tool to navigate rapid chord changes with innovative flair, transforming the way music was played and heard.

When it comes to improvisation over tritone substitutions, various scales can be employed. These include the Altered (Super Locrian) scale, Half-Whole Diminished scale, Whole Tone scale, Phrygian Dominant (Mixolydian b2 b6), and Lydian Dominant Scale.

Navigating tritone substitutions in improvisation involves thoughtful scale choices, adding layers of complexity and color to your solos. This section will discuss how to approach scale selection when dealing with tritone substitutions.

The sharp-11 and lydian dominant scale #

The Lydian Dominant Scale, a mode of the melodic minor scale, features a sharp eleventh (raised fourth) and a dominant seventh. This scale offers a bright yet unresolved sound, aligning perfectly with the tension and release dynamic of tritone substitutions.

The altered scale #

The Altered Scale, also known as the Super Locrian, is derived from the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale. It's characterized by its [altered notes] (b9, #9, #11, b13).

Notice how these altered notes, which are outside of our home key, actually fit nicely within the tritone’s corresponding key.

Diminished scales #

The Half-Whole Diminished Scale is built on a series of alternating half and whole steps. This scale is symmetrical and aligns well with the symmetrical nature of tritone intervals, offering a balanced yet tense sound over dominant chords. Because of its symmetrical structure and the tension it introduces, it's frequently employed over dominant chords.

In fact, the half-whole diminished scale is the same for both dominant chords, making it a logical choice:

Example Exercise:

Practice alternating between F7 and B7 and practice improvising using the shared half-whole diminished scale. Observe how it complements the underlying chord changes and expands your soloing options.

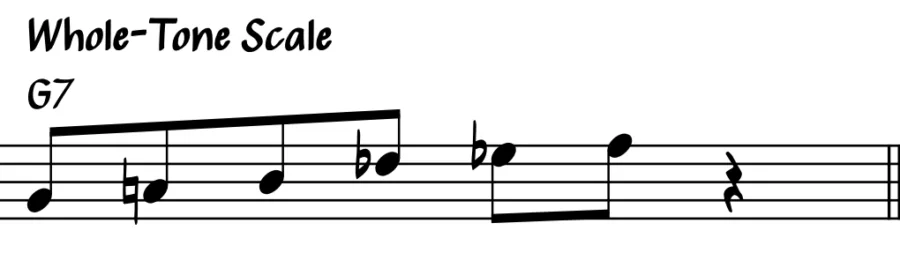

Whole tone scale #

The Whole Tone Scale, made up entirely of whole steps, offers a dreamy and unresolved sound. Its use over tritone substitutions creates a floating, ambiguous sonic landscape, ideal for adding a sense of mystery to a progression.

Similar to the half-whole diminished scale, the same whole tone scale can be applied to both chords:

Phrygian Dominant #

Also known as the Phrygian Dominant Scale, the Mixolydian b2 b6 is derived from the fifth mode of the harmonic minor scale. It features a flat second, sixth, and seventh, akin to the alterations found in the tritone substitution chord, namely the flat-9 and flat-13, contributing to its tonal similarity.

Adjusting improvisation and melody #

The tritone substitution can open up all kinds of new creative direction, giving you the ability to use nearly all 12 notes of our chromatic scale within your solo. However, we cannot ignore the most important constraint: the melody.

Perhaps the most important harmony rule is considering how it fits the melodic line. Harmony is more flexible than melody, which typically is not as fungible.

You must take great care to ensure your choices for chord voicings and scales do not clash with or distract from the melodic line.

When this happens, it's up to you to use your best judgment to adjust the harmonies to support the melody.

Rootless voicings #

Piano and guitar players often play rootless voicings, which omit the root note of a chord, focusing instead on the 3rd, 7th, and other extensions or alterations. This technique is especially useful in combo settings where the bass player covers the root.

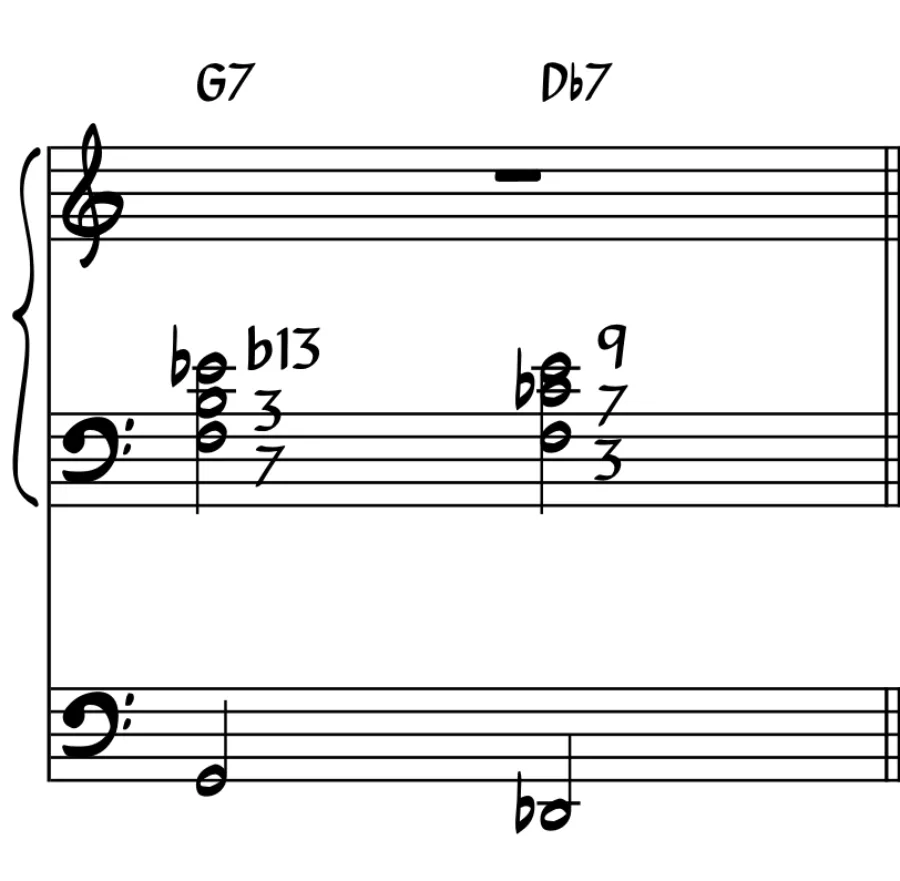

It's interesting to see how these voicings translate across tritone substitutions. Consider a common G7 rootless voicing, where we play the F (7th), B (3rd), and Eb (b13).

This same voicing works over the tritone substitution of Db7. As we already know, the 3 and 7 are the same between the chords (they just trade places). Similarly, most extensions and alterations behave in a comparable manner. In this case, our flat-13 (Eb) in G7 becomes the 9th of Db7.

As long as the notes of your rootless voicing fit the melody, you don't need to change anything to play over the tritone substitution.

The tonality of the specific dominant chord obviously changes; the b13 dominant chord has a spicier sound than the more consonant 9th in the tritone chord, but this is very useful nonetheless.

Common chord progressions with tritone substitutions #

Our common jazz vocabulary includes many progressions that feature a dominant resolution. A tritone substitution can be used as an alternative to any of those dominant chords, provided it works with the melody.

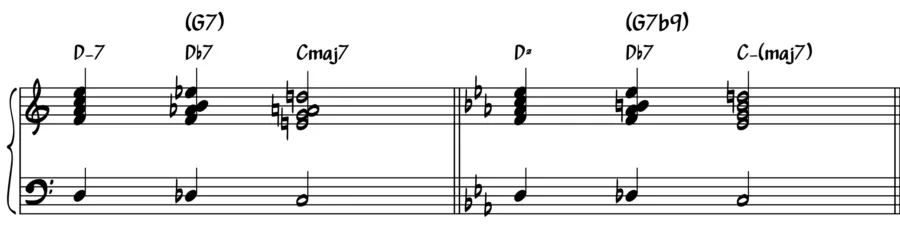

Major and minor ii-V-I #

The ii-V-I progression, foundational in jazz, transforms into a compelling chromatic bass movement by swapping the V for its tritone. It works just as well in minor:

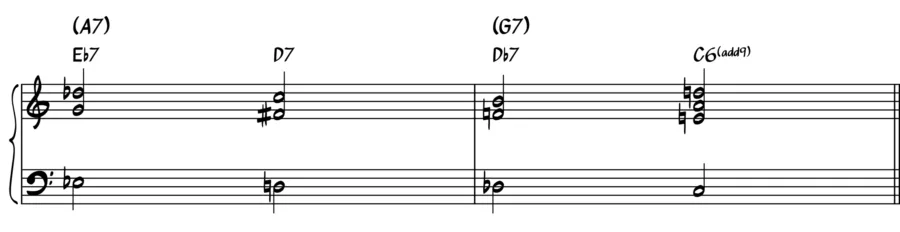

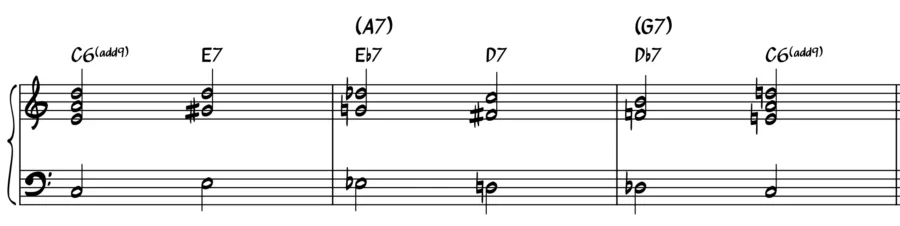

Turnaround #

Turnarounds are common places to introduce tritone substitutions. Essentially, turnarounds are an extension of the ii-V-I progression, achieved by preceding the ii with its V, which is the vi chord.

Although the vi chord is often minor, in this case, using a dominant chord allows for the tritone substitution of one or both dominant chords.

Extended turnaround #

This movement can be further extended by preceding the VI with its V, this time involving the iii chord. Again, while the iii could be minor, in this case, we'll make it dominant here and continue the developing chromatic bass line.

Using the tritone substitution in a blues #

A characteristic of the 12-bar blues is that all the chords are dominant. Given the well-established blues formula, substituting those chords with their tritones is generally not recommended.

However, we hear tritone substitutions in the blues all the time. In fact, it's so common, almost cliché, that many musicians don't even realize it's what they are playing.

The trick is not to use the tritone substitution as a substitute at all, but rather as a passing chord. Put more simply, we precede a blues chord with its dominant counterpart a half-step above.

Here's an example using injected tritone substitutions in the first 4 bars of the blues. In this case, the F#7 is a passing tritone substitution for the C7, and the Db7 is a tritone substitution for an implied G7.

Practically speaking, most musicians I know just think about this as a dominant chord that creates tension and resolution by half-steps. Speaking of which...

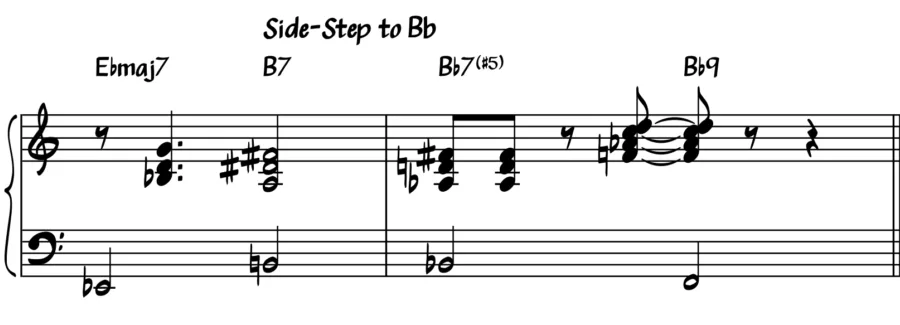

The side-stepping technique #

The idea we explored in the blues—using the tritone substitution as a passing chord that leads into the next, rather than as a replacement—is applicable virtually anywhere.

Any time we want to introduce a sense of tension and release, some gravity towards resolution, precede the target chord with a dominant chord a half-step above, like this:

In the example above we use a B7 chord, which is a half-step above the Bb7 that follows. That B7 acts as a tritone substitution for Eb7, the secondary dominant to Bb7.

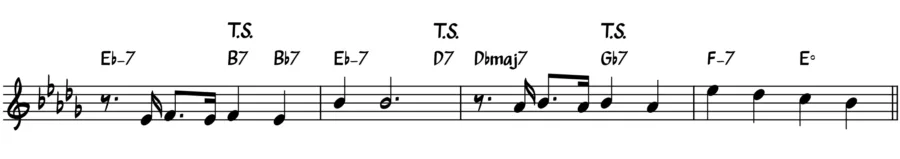

The tritone substitution inside Body and Soul #

There are tons of jazz standards in our repertoire that have tritone substitutions baked right into the changes, but one of my favorites is Body and Soul by Johnny Green.

Here in just the first four measures we find three tritone substitutions (marked "T.S."):

Take a look at the the D9 substitution in the 2nd measure. Our dominant chord is leading us to the Dbmaj7 in measure 3. As discussed earlier, we have two dominant chords which can get us there.

- We could use Ab7, which would resolve down a fifth.

- Or, we could use Ab7's tritone, which is D, which is what we see here.

The easy way to spot this is just to look for that dominant chord which resolves down a half-step -- it's a telltale sign. And look what happens again in measure 3 into measure 4. That Gb7 that resolves to Fm7, down a half-step, is indeed another tritone substitution.

Frequently Asked Questions #

What is a Tritone Substitution? #

A tritone substitution is a jazz harmonic technique where a dominant chord (V7) is replaced by another dominant chord located a tritone interval away. This substitution maintains the tension and resolution characteristic of the original chord but adds a unique, chromatic twist to the progression.

When is the Best Time to Use a Tritone Substitution? #

The best time to use a tritone substitution is typically in a dominant chord that resolves down a perfect fifth. It’s particularly effective in ii-V-I progressions, turnarounds, and places where you want to introduce harmonic variety or complexity.

Can Tritone Substitutions Be Used in Any Musical Genre? #

While tritone substitutions are most commonly associated with jazz, they can be creatively incorporated into other genres like blues, pop, and even classical music. The key is to understand the harmonic context and how the substitution affects the overall progression.

How Do Tritone Substitutions Affect Improvisation? #

Tritone substitutions expand the harmonic palette for improvisation, allowing musicians to explore “outside” notes and create tension before resolving back to the main key. They encourage a more adventurous approach to soloing, stepping beyond the boundaries of the conventional scale.

Are There Any Pitfalls to Avoid When Using Tritone Substitutions? #

One common pitfall is overusing tritone substitutions, which can lead to a loss of the original harmonic intent of a piece. It’s important to use them judiciously and always consider the overall musical context. Additionally, clear communication with band members is crucial, especially in ensemble settings, to ensure cohesive harmonic execution.